For Comfort on a Budget; GU’s PJs Are Popular Among Japanese Girls

Sponsored Links

So far in these series, we’ve followed the trajectory of “kawaii”(“cute”) culture since its appearance in consumerist society from the 1970s. Consumerist society turned “kawaii” into a symbol and then through commercialization, and continued to revamp and reinvent it to target girls’ desires. Up until now, we’ve seen how media aimed at girls, such as an・an, JJ, and Olive all played a role during this time. All of a sudden the “kawaii” movement was dominating Japan’s youth culture, which I have proposed calling the First Kawaii Revolution, or First Cute Revolution.

これまでこの連載では、70年代以降の消費社会の到来とともに現れた「かわいい」カルチャーの軌跡を追いかけてきた。消費社会は「かわいい」という言葉を記号にし、商品化することで、少女たちの欲望の対象を絶えず刷新し、作り出してきた。その時「an・an」や「JJ」、それから「オリーブ」といった少女向けのメディアが一役を担ったことはこれまで見てきたとおりだ。こうした突如として出現し、日本の若者文化を席巻した「かわいい」ムーブメントのことを、私は第一次「かわいい」革命と呼ぶことを提唱したのだった。

Read the previous volume/前回の記事を読む

Following Seiko Matsuda, Idols Come Programmed with Cuteness : The “Kawaii 2.0” Theory vol.8

Read older posts

vol.1 : Finding Where “Cuteness” Currently Lies

vol.2 : What is the Exact Origin of “Kawaii”?

vol.3 : Kawaii Culture Didn’t Exist at the Beginning of the Modern Age?!

vol.4 : Consumerist Society and the Birth of “Kawaii” Culture

vol.5 : The Word “Kawaii” Becomes Just for Girls, to Re-affirm Their Girliness

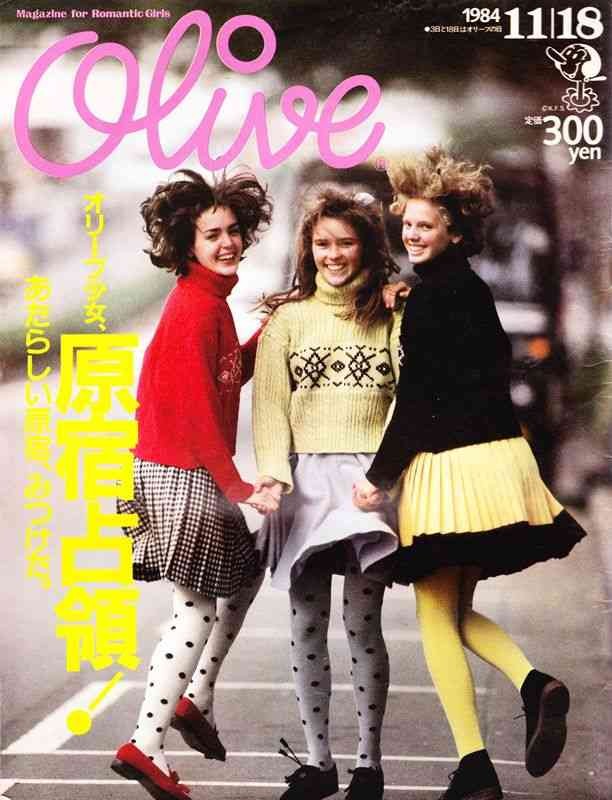

Vol.6 : The Magazine “Olive” Made Japanese Girls Aware of The Rare Value of Girlhood and Maidenhood

Vol.7 : Just Who Exactly Was Momoe Yamaguchi, the Popular Idol Who “Sang” Realistic Stories About Everyday People?

The First Kawaii Revolution, broadcast alongside idols on TV, was able to complete its first mission. At this point the 80s end and the 90s begin. Here, a different “kawaii” culture from that in the past begins to take shape. This is where the story of the Second Kawaii Revolution starts.

第一次「かわいい」革命は、それがアイドルとともにブラウン管のなかに映し出されることで、そのミッションをコンプリートした。80年代の終わりのことである。そして、90年代。これまでとは異なる「かわいい」文化が姿を現し始める。ここからは第二次「かわいい」革命のストーリーだ。

The story of Olive’s kind of romantic “kawaii” ceases to continue on as it had before. The idol craze began to wane, and it was countered and replaced by singer songwriters and punk rock bands who were making waves in the charts. The consumerist targets the First Kawaii Revolution had created had suddenly stopped appealing to people’s desires.

「オリーブ」のロマンティックな「かわいい」の物語はこの頃になると以前ほどには機能しなくなった。アイドルの流行も下火になり、ヒットチャートを賑わせるのはそのカウンター的な存在であるシンガーソングライターやパンクロックバンドに取って代わった。第一次「かわいい」革命で生み出された消費対象はすでに人々の欲望を動かさなくなっていたのだ。

Olive’s kind of romantic “kawaii” / magnif

That said, there is no lapse between the First Kawaii Revolution and the Second. Moreover, the Second Kawaii Revolution isn’t born out of rejecting the First. Instead, the latter takes shape and makes its advance by improving, or “updating”, the former.

とはいえ、第一次「かわいい」革命と第二次「かわいい」革命はその間に断絶があるわけではない。ましてや、後者が前者を否定する形で起きるわけでもない。むしろ、後者が前者をアップデートする形で進んでいくのだ。

So, this means there needed to be some kind of bridge between the two. But who, exactly?

だとすると、第一次と第二次の革命のかけはしのような存在が必要となる。果たしてそれは何者なのだろうか。

Let’s go back in time a little bit. During the “kawaii” culture of the 70s, there was one brand that was born out of Harajuku. On this particular brand’s homepage, which is still around today, you can read the story of its birth, which should be aptly titled, “Genesis”.

少し時間を戻そう。70年代の「かわいい」カルチャー勃興期に、原宿に生まれたひとつのブランドがある。現在も続くこのブランドのホームページには、創世記ともいうべき、誕生の物語が綴られている。

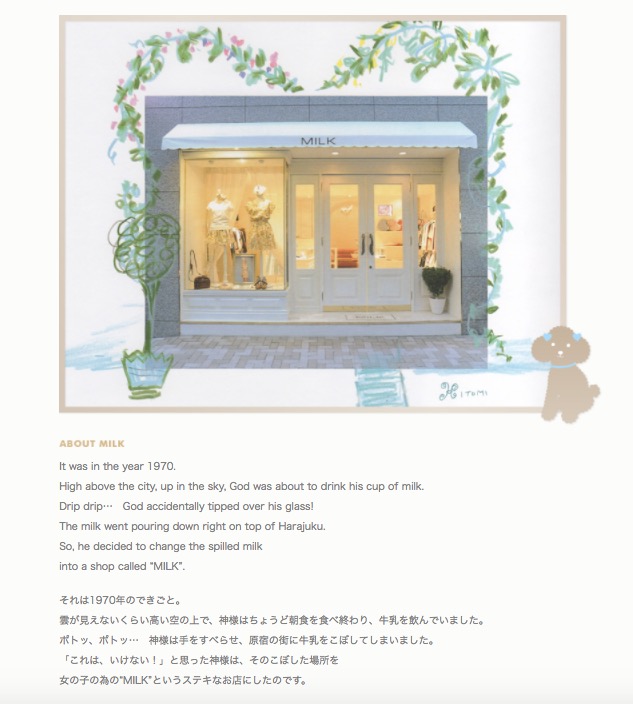

“It all started with something that happened in 1970. Up in the skies of the Heavens, visible to no man, God had just finished breakfast and was drinking the rest of his milk. Plip, plop… The glass slipped out of his hand and drops of milk spilled out of it into Harajuku. “This is terrible!”said God, and so in the spot of Harajuku where all the milk had fallen, God put a magical store there for girls called MILK.”

「それは1970年のできごと。雲が見えないくらい高い空の上で、神様はちょうど朝食を食べ終わり、牛乳を飲んでいました。ポトッ、ポトッ… 神様は手をすべらせ、原宿の街に牛乳をこぼしてしまいました。「これは、いけない!」と思った神様は、そのこぼした場所を女の子の為の“MILK”というステキなお店にしたのです。」

Screenshot from MILK website

At MILK, the tiny shop made from the milk that spilled over from the heavens, Director Hitomi Okawa’s designs attracted much attention, and soon the shop became a big hit. The milk color-based women’s clothing made by Okawa were bursting with individuality not seen in other Japanese brands, and immediately captivated girls across the country who wanted to be cute. The inside of the shop was also the same, simple milky color, and its narrow three-mat size made it feel safe and secure like a little girl’s room. It was the first time Harajuku culture and “kawaii” culture had been meshed together.

雲の上の神様がこぼした牛乳が小さなお店に変わったというMILKは、ディレクター大川ひとみのデザインが注目を浴び、瞬く間に大人気となった。大川の作るミルク色を基調とした女性用の衣類は、他の日本のブランドにはない圧倒的な個性を備え、可愛くなりたい全国の少女たちをたちまち虜にした。店自体も、乳白色のシンプルな内装で、3坪ほどの狭さが逆に女の子の小さな部屋にいるような安心感を与えるような作りになっていたのだ。原宿カルチャーと「かわいい」カルチャーが融和した最初の出来事だった。

Today, Harajuku is full of fancy shops and famous Japanese brands, and the place to feel closest to “kawaii” in Tokyo. However, when Okawa first set up her shop there, it only had a handful of goods and coffee shops, and its streets were not nearly as lively as they are now. Nonetheless, along with MILK there was Leon, a café where creative-types would gather, and the Harajuku Central Apartments that cultured types would use as offices, and out of these cultural magnetic fields you could say that the Harajuku culture that continues on today was born.

今でこそ、原宿はファンシーショップや日本の有名ブランドが混在する、東京でもっとも「かわいい」を身近に感じられる街となっている。だが、大川が店を構えた頃の原宿は、グッズ屋や喫茶店などが数えるほどしかなく、今ほど賑やかな街並みではなかった。それでも、MILKをはじめ、クリエイターの集まる喫茶店レオンや、文化人の事務所が集まるセントラルアパートなどがあり、こうした文化的磁場のなかから今に続く原宿カルチャーが生み出されて行ったのだろう。大川はあるインタビューで当時の原宿を回想し、次のように答えている。

“Harajuku is a great place, with the kind of free atmosphere that invites you in with a ‘Welcome’. In grown up terms, it’s got the same feel as everyone’s favorite pub. For young adults, at every corner there’s a shop catering to their interests and hobbies, and there they can freely talk about them without it being seen as strange. ”

「原宿のいいところは、自由で “ウェルカム”な雰囲気があるところ。大人で言えば、行きつけの飲み屋みたいな感覚なんですね。それが若いコにとっては原宿で、街角に行けば誰かがいたり、趣味の合うお店で好きな会話をしたり、自分がナチュラルに受け入れてもらえる場所なんですよ」

For example, Kyoko Koizumi in her essay, “One-Hundred Scenes of Harajuku”, reflects on her youth spent there, writing about the day she casually went in to MILK and became acquainted with Ms. Okawa. Once in an interview, fashion designer Hiroshi Fujiwara, who had a huge influence on Tokyo street fashion in the 80s, nostalgically talked about how he would visit the MILK atelier shop everyday.

例えば、小泉今日子も原宿で過ごした青春時代の想い出を綴ったエッセイ『原宿百景』のなかで、MILKにふらっと遊びに行き、大川と親しくなった日のことを書いている。80年代の東京におけるストリートカルチャーに絶大な影響を及ぼしたファッションデザイナーの藤原ヒロシも、あるインタビューで当時は毎日のようにMILKのアトリエへ遊びに行っていたことを懐かしみながら話している。

In short, Harajuku’s “kawaii” culture started with MILK, and grew along with it. Then as the brand matured in the 90s, MILK remained as a guardian of this “kawaii” culture.

つまり、原宿の「かわいい」カルチャーはMILKから始まり、MILKとともに育ってきたのだ。そして、ブランドとしての成熟を迎えた90年代、MILKは「かわいい」カルチャーの保護者のような存在となっていた。

Then in the 90s, so-called “blue letter” magazines were launched one after another. These blue letter magazines were different from the feminine-seeking “red letter” magazines (named after the red letters used for their titles) like JJ and an・an that came before them, and were aimed at casual girls, featuring street fashion from Harajuku and the like. Next time we’ll take a closer look at the relationship between blue letter magazines and “kawaii” culture, where you’ll see that MILK appeared a number of times in CUTiE, a leader among these magazines. I’ll introduce to you MILK’s special feature in its April 1990 edition, titled “I think I’m in love with MILK”. The model dressed in this feature’s MILK fashion is Riho Makise, although she was still unknown during this time. Even Soen, a well-established magazine and medium for Japanese women’s high fashion style that just welcomed its 80th anniversary, featured a 20-page editorial on Hitomi Okawa for their April 1990 issue.

90年代になると、いわゆる青文字系という雑誌が続々と創刊される。青文字系雑誌とは、既存の「JJ」や「an・an」といった女性らしさを追求した赤文字系の雑誌(雑誌タイトルが赤色だったことからそのように呼ばれる)とは別路線の、原宿などのストリートファッションをフューチャーしたカジュアル志向の女の子のための雑誌だ。青文字系雑誌と「かわいい」カルチャーの関わりは次回詳しく見るとして、ここでは、その代表的な雑誌である「CUTiE」に度々、MILKが登場していたこと、1990年4月号にはMILKの大特集企画「やっぱりミルクが好き」が組まれていることを紹介しておこう。なお、この特集でMILKのファッションを纏っているモデルは無名時代の牧瀬里穂である。さらには、日本の女性用のハイ・ファッションモードのメディアとして現在創刊80年を迎える老舗雑誌「装苑」でも、同じく1990年4月号に大川ひとみ責任編集というかたちで20ページにもわたる企画を組んでいる。

But why was MILK able to lead the way for “kawaii” culture? In the sixth volume of this series, I wrote about the “Olive girl”. If we take another look at its details, it’s apparent that MILK had exactly the same elements admired by Olive girls. It had ruffles and fantastical designs. It was similar to Paris and London street fashion. The brand paid extra attention to its accessories and goods. MILK was the direction that Olive girls had set their sights on.

では、MILKはなぜ「かわいい」カルチャーを牽引することができたのだろうか。この連載の第6回では、「オリーブ少女」について書いた。詳しくはそちらを読んでもらうとして、MILKはまさにオリーブ少女が憧れる要素を全て持っていた。フリフリのメルヘンなデザイン。パリやロンドンのストリート・ファッションとの近似性。小物やグッズへの丁寧な気配り。オリーブ少女の目指す方向にMILKがいたのだ。

However, this poses another question. Why was MILK able to keep from fading and why did it continue to be admired by girls, even though the Olive girl romance began to gradually disappear after the 1990s? In an interview with author Novala Takemoto, Ms. Okawa had this to say about MILK’s brand image: “Really, it (MILK) follows fashion at its very core. It’s able to accomplish this without anyone noticing, but for those who see it, they know. Being for girls and all, it has the girly image of cuteness, but is also a little impish like having an angelic side and a devilish one.” (Novala Takemoto, Fetish – Takemoto Novala ALL WORKS)

それではもう一つの疑問。なぜMILKはオリーブ少女のロマンが次第に立ち消えていった90年代に入っても、その色が褪せることなく、女の子の憧れの的でありつづけたのか。大川は作家の嶽本野ばらとの対談でMILKのブランドイメージを次のように語っている。「(MILKは)実は芯のところで流行を追い掛けているんです。ばれないようにやっているんですが、やっぱり見る人が見るとわかるんですよ。女の子だから可愛く、ちょっとポワーンとしていて天使っぽいところに悪魔っぽいところを持っている女の子のイメージ。」(嶽本野ばら『Fetish―嶽本野ばらALL WORKS』)

Indeed, MILK merged with the contemporary fashion of its time, and was able to create a completely new fashion. For instance, Ms. Okawa frequently appeared in the tremendously popular 80s fashion magazine Takarajima. Takarajima was responsible for the creation of a number of music scenes, including the indie/punk rock boom in the later half of the 80s. As soon as MILK became part of this phenomenon, it was already making soft punk-style fashion that attracted girls everywhere. With this foundation laid out, even during the street fashion boom that occurred from blue letter magazines in the early 90s, MILK was able to command a large presence.

MILKは実際、同時代のサブカルチャーと絶妙に融合して、新たなファッションを作り出していった。例えば、大川は80年代のサブカルチャー雑誌として絶大な人気を誇っていた「宝島」に度々登場していた。「宝島」は数々の音楽シーンを生み出し、80年代後半にはインディーズ・パンクロックのブームが起きた。その現象と絡み合うように、いち早くMILKはソフトパンク系のファッションを創り出し、女の子たちを惹きつけた。そうした下地が用意されていたからこそ、90年代の初めに起きた青文字系雑誌によるストリートファッションブームでも、MILKはその存在感を大いに発揮できたのだ。

MILK 2017 MILK website

I’ll go into more detail on this later, but in the later half of the 90s, the gothic lolita boom happens. Here again, MILK will be worshipped by lolita girls as a pioneer. This “girl with an angelic side and devilish side” image is one that likely lined up perfectly with their tastes. In this way, MILK was not only a part of the First Kawaii Revolutionary Period, but was able to keep its influence even when this revolution’s flame had burnt out in the 90s. At the eve of the Second Kawaii Revolution at the beginning of the 90s, MILK was there. The meaning of this will gradually become more evident as we delve into the details of the Second Kawaii Revolution, which we’ll reveal in the next volume.

これもまたの機会に詳しく紹介するが、90年代後半になるといわゆるゴスロリブームが起きる。ここでもまたMILKは先駆者的な存在としてロリータ少女から崇められるようになる。「天使っぽいところに悪魔っぽいところを持っている女の子」というイメージが、彼女らのフェティシズムにぴったりあったのだろう。こうしてMILKは、第一次「かわいい」革命期だけでなく、その火が一度燃え尽きた90年代に入っても、影響力を失うことはなかった。90年代の始まり、第二次「かわいい」革命の前夜にMILKがいた。そのことの意味は、第二次「かわいい」革命の内実を迫るにつれて、次第に明らかになっていくだろう。

Translated by Jamie Koide

Sponsored Links

Especia to Break Up in the End of March 2017

Risa Satosaki Reveals Everything in the MV for “S!NG”!