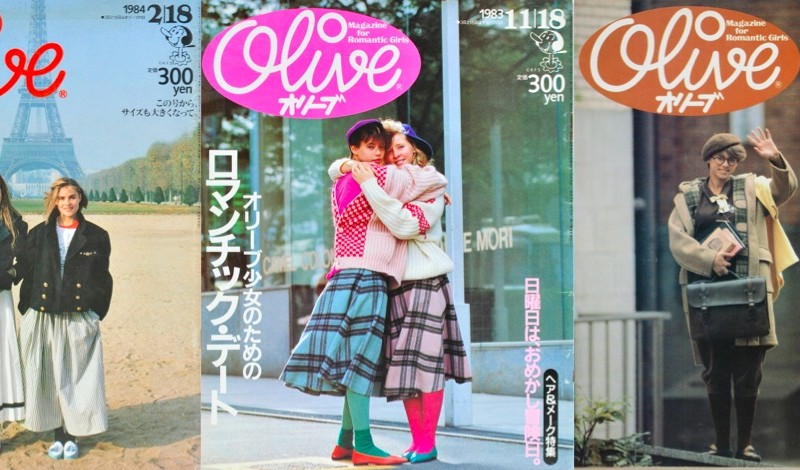

The Magazine “Olive” Made Japanese Girls Aware of The Rare Value of Girlhood and Maid...

![[NEW SERIES] Finding Where “Cuteness” Currently Lies – The “Kawaii 2.0” Theory vol.1](https://tokyogirlsupdate.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/eyecatch.jpg)

Sponsored Links

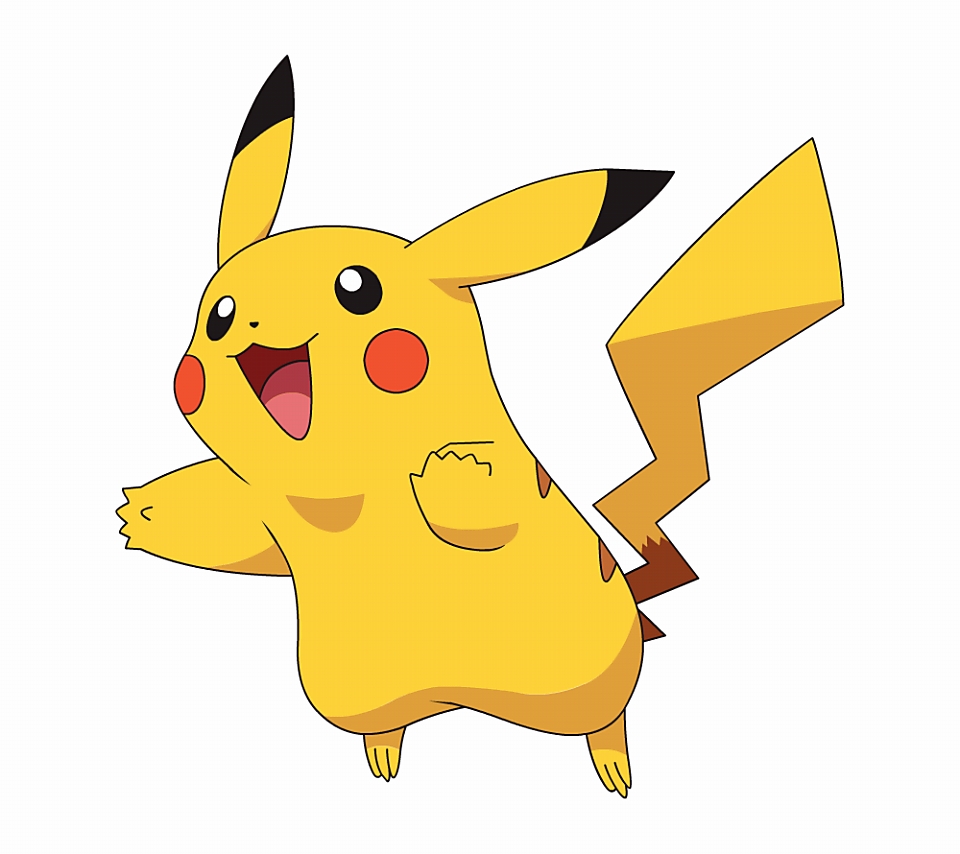

Right now Japanese “kawaii” (“cuteness”) is changing. Rather, it has already changed. Or, what should I say, is that the face of what is “kawaii” is always changing. In any case, many of the discussions that have come up concerning “kawaii” now seem rusty, and already a thing of the past. So it would seem that it’s time to update this “kawaii” theory with what is currently favored now.

いま、日本の「かわいい」に変化が起きている。いや、すでに起こってしまったというべきか。あるいは、「かわいい」は絶えずその姿を変え続けているというべきなのか。とにかく、これまで、さまざまなところで交わされてきた「かわいい」の議論は既に、錆び付いて、時代遅れのものになっている感じが否めない。現在求められているのは、この「かわいい」論をアップデートすることなのではないだろうか。

I understand this might sound like I’m exaggerating, and I’m not sure how much of this will be reliable. Or what I mean is, at the moment there is nothing currently outlining this new “kawaii” now. Therefore, it is necessary to carefully take the time to outline my own.

と、大きな風呂敷をとりあえずは広げてみたが、果たしてそれをどれだけ回収できるかわからない。というのも、この「かわいい」の現在を見渡せる地図が、どこにもないからだ。そのため、これからじっくりと時間をかけて、「かわいい」の見取り図を描いていかなくちゃいけない。

For example, according to previous theories of “kawaii”, it has been said that “kawaii” is a special word in Japanese, and a unique concept affirming childish and young things. In the book by Inuhiko Yomota, Kawaii Theory, which thoroughly explores and traces the origins of Japanese “kawaii”, it says, “Inside Japanese culture, the tradition of giving an affirmative meaning to small or childish things has survived, and should be kept in mind,” and comparing the values between Japan and the West when it comes to childish things, that “it differs in the West, where childishness is seen as a stage toward reaching maturity, and is looked down upon.”

例えば、これまでの「かわいい」論で言われてきたことは、日本の「かわいい」というのは特殊な言葉で、それじたい未成熟なものや幼いものを肯定するユニークな概念だ、ということだった。批評家の四方田犬彦は、『「かわいい」論』という日本の「かわいい」を起源からさかのぼってそのエッセンスを徹底的に考えた本のなかで、「日本文化の内側に小さなもの、幼げなものを肯定的に意味する伝統が確固として存続してきたことは、やはり心に留めておくべきだ」と言い、「それは欧米のように未成熟を成熟への発展途上の段階と見なし、貶下(へんげ:「見下す」という意味)して裁断する態度とは、まったく異なる」と、日米の未熟なものに対する価値観を比較している。

I do not know if Western culture really looks down on childish things or not. I personally don’t think that’s the case. However, it’s true that the word “kawaii” was originally used to express positivity toward small and childish things, and that it served as the foundation for miniature “kawaii” monsters like Pokemon to become a part of Japanese culture.

はたして欧米の文化では、未成熟なものを見下す傾向があるのかどうかはわからない。私自身は、そんなことないんじゃないか、と思っている。ただ、日本においては、「かわいい」がもともと小さいものや未成熟なものを肯定する言葉であったことは確かなようだ。ポケモンなどミニチュアの「かわいい」モンスターが日本文化のなかで誕生するのは、そういう土台があってのことだったのだし。

Pikachu

That said, currently “kawaii” is evolving. Just thinking of “kawaii” as a positive affirmation for small and immature things isn’t enough. It has surprisingly transformed into a multitude of concepts, which is why I wanted to title this piece as “Kawaii 2.0”, in order to differentiate what “kawaii” is currently with what it has been up until now. But what exactly is this “kawaii 2.0”?

しかし、現在、「かわいい」は進化している。小さいものや未成熟なものを肯定する言葉、と考えるだけでは十分に「かわいい」の正体をつかめない。それは驚くほど多様な概念となっているのだ。そこで、まず、現在の「かわいい」をこれまでの「かわいい」とは異なるフェーズに移行したという意味を込めて、「かわいい 2.0」と名付けてみよう。この「かわいい 2.0」とはいったい何だろうか。

In any case, “kawaii 2.0” is peculiar for the fact that it’s now so diversified that just describing it in one word as “kawaii” is almost completely meaningless. For example, “yume kawaii” (“dreamy cute”) is currently a hot topic in modern girls’ culture, and if you were to dare to call something grotesque to be cute, it would be “kimo kawaii” (“creepy cute”). Furthermore, things that appeal to male sexual desire or erotic things are categorized as “ero kawaii” (“erotic cute”). In this way, you could say that what we’re currently witnessing now is “kawaii” subdividing itself, like the continued self-procreation of amoeba cells. Because of this, “cute” no longer refers to small or childish things. In a sense, things that are considered erotic are already mature, and things that are called “yume kawaii” have hardly any trace of reality, referring to some kind of fantastical world.

「かわいい 2.0」はとにかく現在、「かわいい」が多様化しすぎているあまり、ひとこと「かわいい」と言っただけでは、ほとんど意味をなさない、という特徴をもっている。例えば、現在のガールズカルチャーにおけるホットトピックである「ゆめかわいい」。それから、あえてグロテスクなものを「かわいい」と認めてしまう、「キモかわいい」。さらには、男性の性的な欲望を刺戟するようなエロティックなものを「かわいい」とカテゴライズする「エロかわいい」。こうして、「かわいい」が内部で細分化して、まるでアメーバの細胞のように自己増殖し続けている事態を、現在私たちは目の当たりにしているのだ。そこでの「かわいい」対象は、もう、小さいものや未成熟なものではない。エロティックなものというのは、ある意味では成熟したものであるし、「ゆめかわいい」と呼ばれるものはリアリティを極力薄めた、幻想的な世界のことを言うのだから。

Announcement for Yume Kawaii exhibition

Kimo Kawaii CD jacket of Karry Pamyu Pamyu

Ero Kawaii

Additionally, with “kawaii 2.0”, I believe “kawaii” consumed as global content and what is treated as “kawaii” in the Japanese girls’ culture scene branches off in two different directions. To put it simply, the “kawaii” that is consumed as global content is “kawaii” that has evolved domestically, gotten caught in the vortex of globalism, and been translated, and has become distributed as a form of soft power from Japan.

また、「かわいい 2.0」では、グローバルコンテンツとして消費されている「kawaii」と、国内でガールズカルチャーのシーンで使用されている「かわいい」がふた方向に分岐していると考える。このグローバルコンテンツとしての「kawaii」とは、簡単に言えば、日本文化の内部で進化を遂げてきた「かわいい」がグローバリズムの渦に巻き込まれて、翻訳され、日本のソフトパワーとして流通するようになったものだ。

So, when people think of “kawaii” as a unique part of Japanese culture, it’s connected to the image of the “kawaii” being consumed abroad, and vice versa. For example, why Pokemon was created or why Hello Kitty is so popular with high school girls (JK), when discussed, will be naturally be taken for Japanese exoticism, and is the reason “kawaii” has seen such rampant consumption overseas.

だから、日本文化独自の「かわいい」を考えることは、海外で消費されている「kawaii」を考えることにもつながってきていたし、その逆もまたしかり、だったわけだ。例えば、なぜ、日本でポケモンが誕生したのか、あるいは、ハローキティが女子高生に人気があるのか、を議論することが、自然と日本のエキゾチシズムを取り出すことになり、それがそのまま海外における「kawaii」の爆発的な消費の理由としても、通用したのだ。

Hello Kitty

But the whispers of “kawaii” from Japanese girls has largely evolved from that, and to some extent is currently differentiated by translating the word as “kawaii” overseas and “かわいい” (“kawaii”, but written out in Japanese instead) within Japan. Perhaps it could be said that at one time they were identical twins, but at some point only “かわいい” transformed into something more multi-faceted.

だが、国内で女の子の間でささやかれる「かわいい」はそれから大きく進化を遂げてきため、ある時点までは海外版「kawaii」は国内版「かわいい」の翻訳姿だったのが、現在は、その二つが乖離してしまっている。イメージとしては、一卵性双生児だった「かわいい」と「kawaii」が、いつのまにか「かわいい」の方だけ姿を変え、いろんな表情をするようになった、みたいな感じだと言えばいいだろうか。

So in this series, we’ll examine the original concept of “kawaii”, outlining it from its beginnings until its current state. Or to summarize, once again, we’ll trace the step-by-step evolution of “kawaii” from its origin as much as possible, in order to grasp its true character. Then we’d like to try and approach what exactly the current diversification of “かわいい”, or “kawaii 2.0” is. Additionally, women are now expressing their dislike or being called “kawaii”, and in certain situations, consider using the word “cute” recklessly as a form of gender-related violence. We’re planning to make the topic a ten-article series. After concluding the tenth installment, I’d like to share my embarrassing experience of talking about “kawaii” whilst unaware of it with all of you readers.

というわけで、この連載では、「かわいい」史上もっとも多様化しているこの概念の、過去から現在までの見取り図を作ろうと思う。ようするに、もう一度、「かわいい」の起源からその進化の段階で起きた出来事をなるべく丹念に追って行って、「かわいい」の正体をつかみたい。そして、現在の多様化した「かわいい」、つまり、「かわいい 2.0」という事象がいったい何を意味しているのかについて迫りたいと思う。さらには、現在、「かわいい」と呼ばれることを忌み嫌う女性たちが出てきているという実感がある。その背景にある、「かわいい」とむやみやたらに表現することの暴力性を考えていく。全部で10回ほどの連載を予定している。その10回を終えたとき、「かわいい」を無自覚に唱えていた自分が恥ずかしくなるような体験を、読者のみなさんとともにしたいと思う。

Cover Photo by Kenta Kuzuhara

Translated by Jamie Koide

Sponsored Links

[Exclusive Program] Tokyo GIrls’ Update TV #006 : SBY in Shibuya109 & Pikarin’s Cosplay

8th Wave of Tokyo Idol Festival 2016 Performers Announced!!