Doing Everything I Wanna Do!: Hello Kitty Makes YouTube Debut

Sponsored Links

Finally, we’ve arrived at the moment where we can begin writing about the moment when “kawaii” culture began. Even though the concept of “girls” existed between the 19th and the first half of the 20th century, “kawaii” culture did not. But from the second half of the 20th century, “kawaii” culture made its explosive arrival. This happened during the span of Japan’s consumerist society.

さて、ようやく、「かわいい」カルチャーの誕生の瞬間について書くときがきた。少女という存在はあっても、「かわいい」カルチャーはなかった、19世紀から20世紀前半。そこから約半世紀が過ぎて、「かわいい」カルチャーは爆発的に誕生するのだ。そう、消費社会という空間のなかで。

We know that Japan’s consumerist society occurred from the 1970s until the end of the 1980s, and was a society made up of people that had begun to consume information and goods related to various products. The value these goods were not measured by their usefulness, but from the brand image they represented and their desirability. So while owning a GUCCI bag would be significant, owning a similar bag without the GUCCI name would not. Though this consumerist society began in he 1970s, it is still influential today.

消費社会というのは、よく知られているように、1970年代から1980年代の終わりにかけて、人々が商品に付随する情報や記号を消費するようになる社会のことだ。そこでは、商品の使用価値それじたいじゃなくて、ブランドイメージなどでその商品の価値が決まり、人々の欲望が作り出されていく。GUCCIのかばんを持つことに意味があるわけで、GUCCIに似たかばんじゃ意味がない。それが1970年代の初めから今に至る、消費社会なのである。

This was around the time when fast food chains like McDonald’s, Mister Donut, and Baskin Robbins and convenience stores started out in Japan. That is, they combined the values of the general public, creating an optimal environment where consumption according to these values was quick and enjoyable. Thus, the flower of “kawaii” culture blossomed during this time.

ちょうどこの頃、マクドナルドやミスター・ドーナッツ、サーティーワンアイスクリームなどのファーストフードやコンビニエンスストアが日本に誕生し始めた。つまり、大衆の価値観がある意味で均一化され、その価値観に従って消費することが手っ取り早く快楽を得る、最適な手段とされるようになっていったのだ。そして、「かわいい」カルチャーが花咲くのもこの時代なのである。

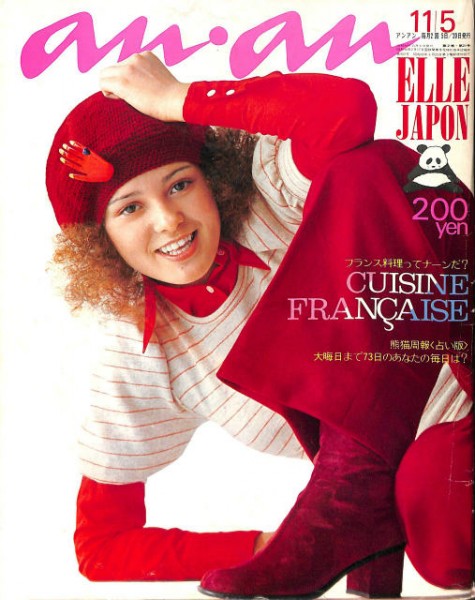

The introduction of so-called fashion and information magazines in succession served as the foundation. The magazines an・an, non・no, and Pia were launched in 1970, 1971, and 1972, respectively. Next time we’ll get into fashion magazine and consumerist society’s involvement with “kawaii” culture, but for now please keep in mind that media that influenced “kawaii” culture was created during this consumerist society period.

そのための土台として、いわゆるファッション誌や情報誌がこの頃になると続々と誕生していった。1970年には雑誌「an・an」が、1971年には「non・no」が、1972年には「ぴあ」が創刊される。ファッション誌と消費社会と「かわいい」カルチャーの関わりについては、次回にでも改めて取り上げるつもりなので、ここでは今後「かわいい」カルチャーを牽引するようになるメディアが消費社会のなかで生まれたとだけ覚えておいてほしい。

So let’s take a closer look at how exactly the bond between consumerist culture and “kawaii” culture came about. First of all, in 1973, a company called the Yamanashi Silk Center renamed itself to Sanrio. I don’t think Sanrio, and subsequently the “Sanrio Miracle” behind the creation of characters one after another like Hello Kitty and My Melody, requires any explanation. At the same time Sony Creative Prodcuts and Gakken, referred to as “fancy businesses”, began to expand their business with “kawaii” character goods, jumpstarting a huge boom.

具体的な消費社会と「かわいい」カルチャーの融合が生み出していったものを見ていこう。まず、1973年に、山梨シルクセンターという会社がサンリオという名前に改称した。サンリオとはのちに「サンリオの奇跡」として、ハローキティやマイメロディなどのキャラクターを次々と生み出して行った会社であることは説明するまでも無いだろう。それから、同じ頃、ソニー・クリエイティブ・プロダクツや学研が、ファンシービジネスと呼ばれる、「かわいい」キャラクターをグッズ展開する商売で大ヒットを飛ばし始めた。

Additionally, the Rika-chan doll, a dress-up doll similar to America’s Barbie, but marketed to Japanese consumers, began to exceed the sales of the Barbie line around 1970. Eiji Otsuka, the same critic we also quoted before, captured this era by saying, “This is when it became possible to sell products based on the symbolic value of their cuteness (‘kawaii’), rather than the value of their usefulness,” making an important point that here things were not created for the sake of creation itself, but created to add in the element of cuteness. In short, “kawaii” culture was born within the consumerist society, with the word “kawaii” just one of many symbols that evoked a sense of desirability among the public, which then led to it becoming a specific item trend.

さらには、リカちゃん人形といった、アメリカのバービー人形を日本人向けに作り直した着せ替え人形が、本家バービー人形の売り上げを上回るようになったのも、1970年頃。前回も引用した大塚英志という批評家は、この時代を捉えて、「モノを直接的な使用価値ではなく「かわいい」という記号価値で売っていくことが可能になる時代の始まりである」と言い、そこでは、「〈モノ〉それ自体の開発ではなく、〈モノ〉に付加する〈かわいさ〉の開発こそが重要課題である」と指摘している。ようするに、「かわいい」カルチャーが消費社会のなかで誕生すると、「かわいい」という言葉はひとつの記号として、人々の欲望を喚起するようになり、それが具体的なアイテムとして流行し始めていったのである。

Additionally, two things were born from the “kawaii” culture created within consumerist society. The first was “non-standard girlish script”, a cute lettering style that became popular among girls. According to the non-fiction writer Kazuma Yamane, this typeface was introduced in 1974, and was heavily adopted by high school girls all across Japan five years later. Yamane says girls imitating fonts used by fashion magazine an・an was a factor behind this, as was the spread of the mechanical pencil, causing the traditional style to take on a roundness to it. There are many who object to Yamane’s theories, but in any case, “kawaii” culture began to encroach upon girls’ culture, and had a significant impact on girls’ handwriting.

この消費社会が作り出した「かわいい」カルチャーのなかで生み出されたものはあと2つある。まず、ひとつは、「変体少女文字」という女の子たちの間で流行った「かわいい」文字のスタイルだ。ノンフィクションライターの山根一眞によると、この書体は、1974年頃に誕生し、その5年後には日本全国の女子高生が使用するようになっていたようだ。山根は、その誕生の要因として、雑誌「an・an」で使われていたフォントを女の子たちが真似し始めたこと、また、シャープペンシルの普及によって従来の文字のスタイルが丸みを帯びていったことという2点をあげている。山根の説にはいろいろ異論を唱える人たちがいるようだが、いずれにしても、「かわいい」カルチャーが少女文化を侵食し、彼女らの書く文字までをも変えてしまったことは事実である。

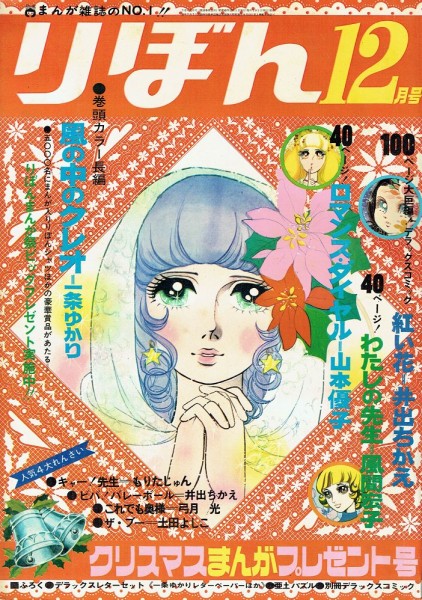

The other was a change in girls’ manga magazines. As Eiji Otsuka continued to study girls’ manga magazines, he noticed that around the 1970s there was a change in the freebies that came with these magazines. Until then photos, posters, and the like of male idols had been bundled inside of them, but in 1975 this changed to pouches and cases with “kawaii” characters from girls’ manga printed on them. Those made with paper served little used in everyday life, as they would soon fall out while carrying them. Thus they had little value as useful items, and instead were valued for the “kawaii” character symbols they displayed. However these items were popular with girls. Otsuka captured the phenomenon with his analysis, “The poor useful qualities of Mutsu A-ko’s (a mangaka) characters = nothing more than the establishment of Ribon’s (a girl’s manga magazine) freebies as “fancy goods” in order to meet the desires of girls overcome with the idea of “kawaii” symbolism,” and he was spot on.

それから、もう一つ、少女まんが誌の変化である。大塚英志は少女まんが誌を研究していくなかで、1970年代中頃になると雑誌についてくる付録が変わったことに気づいたと言う。それまでは、男性アイドルの写真やポスターなどが雑誌に挟まっていたのが、1975年には、少女まんがの「かわいい」キャラクターをプリントした小物入れやケースなどの紙製のグッズに取って代わった。この紙でできた小物入れは、日常品としてはあまりに壊れやすい。持ち歩けばすぐに底が抜けてしまう。使用価値などほとんどない。あるのは「かわいい」キャラクターという記号だけ。しかし、それが女の子たちの間でウケた。大塚はその現象を捉えて、「劣悪な「使用価値」を陸奥A子(注:漫画家)らのキャラクター=記号で克服し〈かわいいもの〉への彼女たちへの欲求に応えようとした『りぼん』のふろくは〈ファンシーグッズ〉の先駆けに他ならなかった」と分析しているが、まさにその通りだろう。

Ribon

So as we see here, consumer society created “kawaii” culture. Following this, “kawaii” culture had a dramatic effect on girl’s culture. This would become a major event that changed women’s everyday perspectives. In order to give more attention to this topic, next time I’d like to delve into the “kawaii” culture involvement of girls’ fashion magazines such as Olive and an・an.

と、ここまで見てきたように、消費社会は「かわいい」カルチャーを生み出した。そして、その「かわいい」カルチャーは少女文化に劇的な変化を及ぼした。それは、彼女たちの日常の光景を変えてしまうような、大きな事件だった。そのことをもう少し考えるために、次回は、「オリーブ」や「an・an」といった女性ファッション誌と「かわいい」カルチャーの関わりについて見ていきたい。

Translated by Jamie Koide

Sponsored Links

Unite the World! BABYMETAL Releases the Anthemic MV for “THE ONE”

Risa Satosaki Reveals Everything in the MV for “S!NG”!