For Comfort on a Budget; GU’s PJs Are Popular Among Japanese Girls

Sponsored Links

On the subject of Japanese magazine culture and girls’ culture, there’s one magazine that can’t be overlooked. It was called Olive, and was founded by Heibon Publishing (now Magazine House) in 1982. This magazine, which appeared during the first wave of the “Kawaii Revolution”, completely stole the hearts of all the high school girls during this period. Translator and essayist Madoka Yamazaki recalls those days and describes them by saying,

日本の雑誌文化、そして、少女文化を語るうえで欠かせない雑誌がある。1982年に平凡出版(現マガジンハウス)から創刊された「オリーブ」だ。第一次「かわいい革命」最盛期に誕生したこのメディアは、当時高校生だった少女たちの心を奪った。翻訳家でエッセイストの山崎まどかは、その頃を回想して次のように語る。

“I really wanted to be like the heroine in this magazine’s story. That was the impression Olive left on me after first reading the magazine when I was 13. I had a burning desire to be the heroine in this magazine, more than just wearing and owning the clothes featured in it. I wanted to be called an “Olive Girl”, like the girls featured in the magazine.” (Madoka Yamasaki, “Olive Girl Life”)

「この雑誌の物語の主人公になりたい。13歳の時、初めて『オリーブ』を読んで、そんな風に思った。ここに載っている服が着たい、欲しいというよりもずっと強い気持ちで。雑誌の中で、『オリーブ少女』と呼ばれているような女の子になりたかった」(山崎まどか『オリーブ少女ライフ』)

I want to be an “Olive Girl”. That was the desire that began to blossom in the hearts of many girls in the 80s. But what exactly did Olive have to do with “kawaii” culture after the first wave of the revolution?

「オリーブ少女」になりたい。それは、80年代の少女たちのなかに芽生え始めた、新しい欲望だった。第一次革命以後のかわいいカルチャーと「オリーブ」には果たしてどのような関係があるのだろうか。

Read the past articles

vol.1 : Finding Where “Cuteness” Currently Lies

vol.2 : What is the Exact Origin of “Kawaii”?

vol.3 : Kawaii Culture Didn’t Exist at the Beginning of the Modern Age?!

vol.4 : Consumerist Society and the Birth of “Kawaii” Culture

vol.5 : The Word “Kawaii” Becomes Just for Girls, to Re-affirm Their Girliness

With the consumerist society that came about in the 70s, the word “kawaii” became a commercialized symbol. “Kawaii” became a target for consumerists, greatly increasing the desire girls felt. And so, magazines and other types of media began to capture this desire and sensitivity in girls. In our last volume we looked at how even now, the magazine an・an is still a leader when it comes to “kawaii” culture.

70年代に到来した消費社会は「かわいい」という言葉を記号にして、商品化した。「かわいい」は消費対象になり、当時の少女たちの欲望を大きく刺激するようになったのだ。こうした少女たちの欲望、あるいは感受性の変化を雑誌などのメディアは絶妙に捉えていた。今でも続く「an・an」などが、かわいいカルチャーをどのようにして牽引していったのかは前回見たとおりだ。

an・an

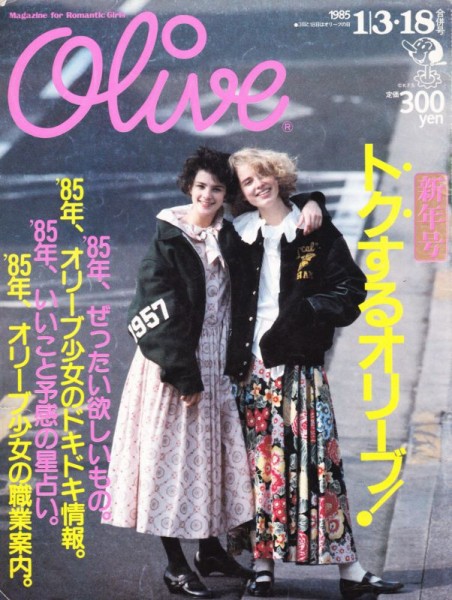

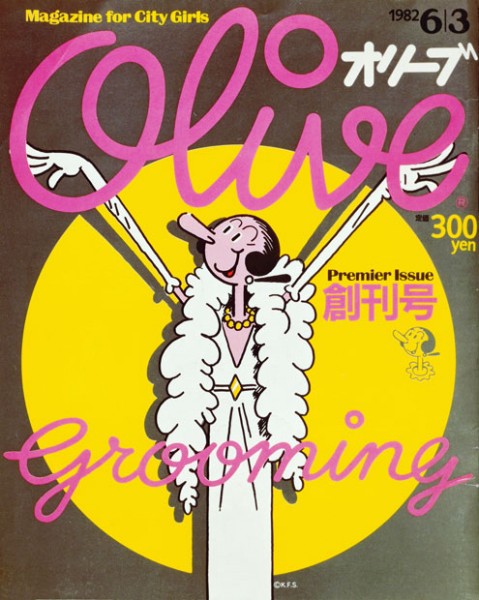

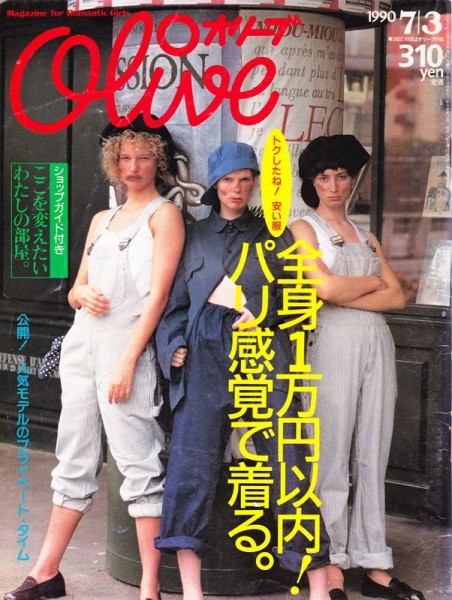

Going into the 80s this trend didn’t decline- it only became bigger. The launch of the magazine Olive is part of the backstory as to why. Originally Olive was published as a special edition of the wildly popular men’s fashion magazine, Popeye. In order to introduce a girls’ version of Popeye in light of the sweeping “city boys” fashion trend, it was launched with the tagline “Magazine for City Girls” and had many casual and stylish features.

その流れは80年代になっても衰えることなく、むしろ勢いを増すかたちで続いた。「オリーブ」が創刊されるのは、そのようなバックグラウンドがあってのことである。そもそも「オリーブ」は男性ファッション誌として、当時人気を誇っていた「ポパイ」の増刊号として刊行された。シティボーイズのための流行を紹介する「ポパイ」の女の子版として、キャッチコピーも「Magazine for City Girls」と打ち出し、中身もスタイリッシュで軽やかなものが多かった。

Olive

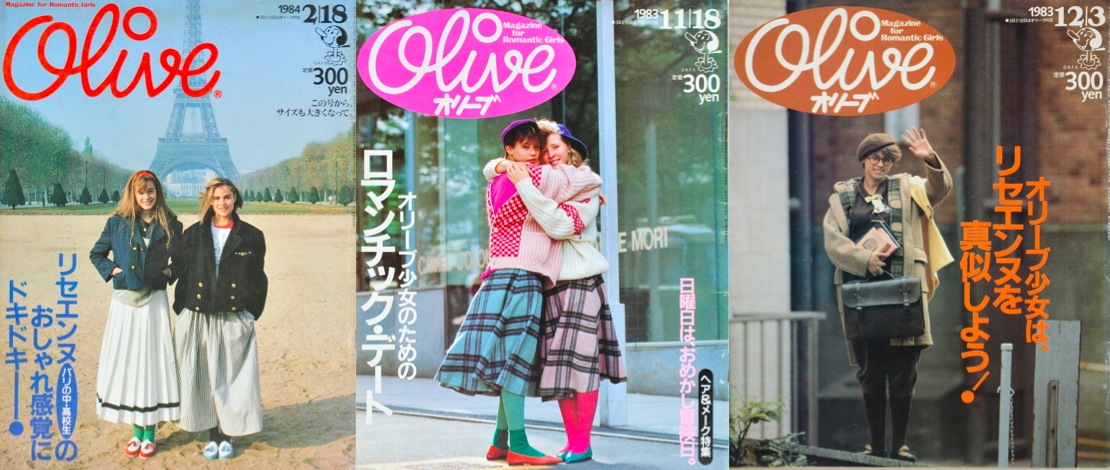

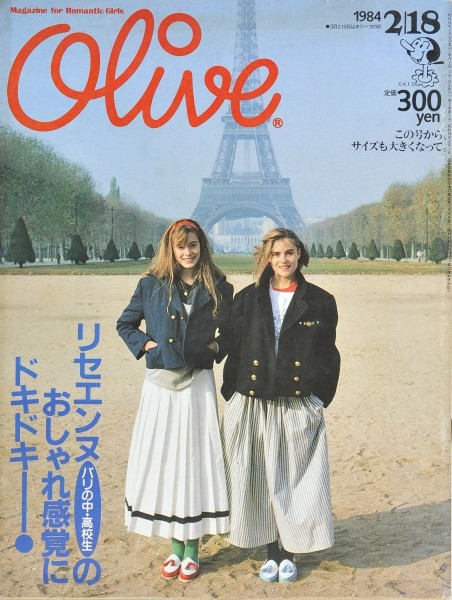

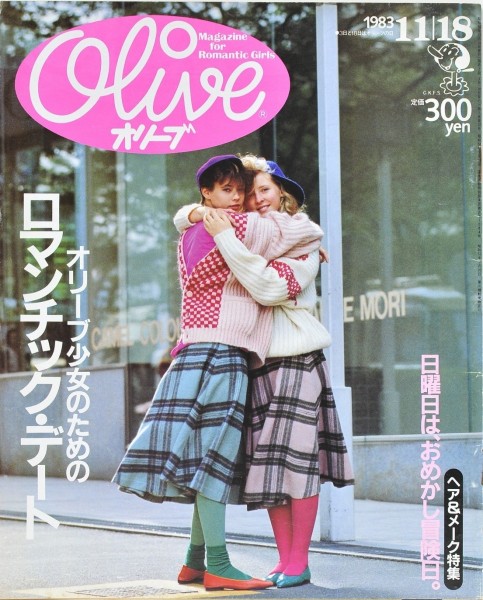

Although the design of the magazine during its first period stuck out from the usual girls’ magazine framework, it suddenly halted publication in 1983. Then, about a month later, it re-debuted after going though a complete overhaul, without any of the city style left that it had before. Instead, it radiated girly romanticism from every page, and changed its tagline to “Magazine for Romantic Girls”. So it went from “City” to “Romantic”. One of the reasons for the magazine’s complete turnaround was the introduction as the “Lyceenne” as the ideal model.

既存の女性誌の枠からはみ出る雑誌としてのデザインが注目された初期「オリーブ」だったが、1983年に突如、休刊する。そして、一ヶ月後にリニューアルして再び登場した時には、以前のようなシティ派の感覚を体現した姿は消えていた。その代わりに、夢見がちな乙女心に訴えかけるようなロマンティシズムをページの隅々から醸し出し、キャッチコピーも「Magazine for Romantic Girls」へと変わっていった。「City」から「Roman」へ。こうした方向転換のなかでひとつのモデルとして提示されたのが「リセエンヌ」だった。

Lyceenne

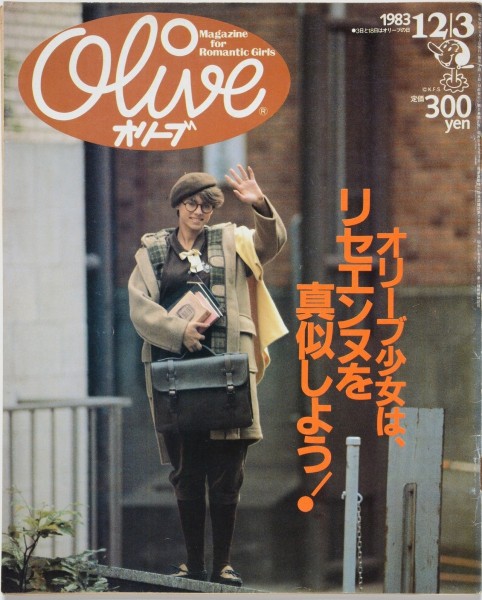

If you look at the Volume 35 of Olive (from December 3, 1983), the cover reads, “Olive Girls try look like the Lyceenne!”. “Lyceenne” means high school girl in French. It referred to a girl who was sophisticated and stylish, like those in Paris. Unlike the American casual fashion it had run before, it was now about not imitating men’s fashion, and girly, chic fashion became its theme. For girls that grew up during this time, the humble image of the Parisienne Lyceenne was what they were supposed to look up to.

「オリーブ」の第35号(1983年12月3日号)を見ると、表紙に「オリーブ少女はリセエンヌを真似しよう!」と大きく書かれている。「リセエンヌ」とは、フランス語で女学生を意味する。パリのような洗練されたオシャレ。これまでのアメリカンなカジュアルさではなく、決して男の人には真似できない、乙女チックなファッション。「リセエンヌ」のような純朴なパリジェンヌこそが、当時の少女たちにとって憧れるべき存在だったのである。

According to fashion researcher Reiko Koga, there were three types of “Olive Girl” styles. First was “dolling yourself up in ribbons and frills, lace, floral prints, and other ‘girlish’ styles. Brands that gave off a fairytale-like feel, such as Pink House by designer Isao Kaneko, were popular with girls that idolized this style. Second was the ‘boyish’ style worn by fashion idols like Kyoko Koizumi and Checkers. Girls would actively try to incorporate London and Paris street fashion into their style, or an ‘anarchistic sense of fashion’. The third type was a style with ‘a strong taste for small items and accessories’.” Koga comments that, “These girls would collect things that appealed to their sense of cuteness, and randomly mix them together in a mismatched manner. This ‘random mix’ expressed their individuality, or their own outlook on the world, but is likely what brought about the fashion sense that would later be referred to as Harajuku fashion.” (from Reiko Koga’s ‘Kawaii’ no Teikoku (The Empire of ‘Cuteness’)

ファッション研究家の古賀令子は、「オリーブ少女」のスタイルを3つに分けて分類している。第一は、「リボンやフリル、レース、花柄など『少女っぽい』装飾志向のスタイル」だ。こうしたスタイルにこだわる少女たちが憧れるブランドには、前回紹介した金子功がデザインするピンクハウスがあり、彼女らの間ではメルヘンチックなファッションが人気となった。第二には、「小泉今日子やチェッカーズといったアイドル・イメージの『ボーイッシュ』スタイル」がある。彼女らはパリやロンドンのストリート・ファッションを積極的に取り入れ、「アナーキーなファッション感覚」を身につけていたという。第三は、「小物やアクセサリー、雑貨への強い嗜好性」を持つスタイルである。古賀いわく、「彼女たちの『かわいい』という感覚で集めたものを、ごちゃ混ぜにミスマッチ感覚で身につける。その「ごちゃ混ぜ」によって、彼女たちは個性、つまり自分の世界を表現していた」わけだが、それは後年原宿系と言われるファッションに引き継がれていった感覚だろう。(以上、古賀令子『「かわいい」の帝国』)

‘girlish’ styles

‘boyish’ style

Thus, the magazine Olive became an indispensible media source when talking about girl’s fashion since the 80s. Junko Sakai, and essayist who has continued her series of writings since the first period of Olive, states that: “Olive, for many Japanese girls who were frivolous with their limited period of girlhood or maidenhood, was a magazine that ‘spoke subjectively to what it was to be a girl’”, and among this, “the ‘Olive’ from the frequently printed words ‘Olive Girl’ taught girls ‘the value of being girls’.”

かくして、「オリーブ」という雑誌は80年代以降の少女文化を語るうえで、欠かせないメディアとなった。初期「オリーブ」から連載を持ち続けたエッセイストの酒井順子は、「オリーブ」とは「少女性、処女性という、その時しか持ち得ないものを無駄遣いしている日本の少女達に、『少女であることに自覚的であれ』と語りかける雑誌」であり、そのなかで「『オリーブ少女』という言葉を頻出させることによって、『オリーブ』は “少女であることの価値”を、読者に教えた」と述べている。

Additionally, being able to remain a girl. In a sense, it was likely a way to rebel against a society that wanted women to be mature. Olive, according to Sakai, was a magazine that played a major role because it “made Japanese girls aware of the rare value of girlhood and maidenhood”.

少女でありつづけること。それはある意味では、女性たちに成熟をもとめる社会への反抗、だったのかもしれない。とにかく、「オリーブ」は、酒井順子が言う通り、「少女性と処女性の稀少価値を日本の少女たちに気付かせた」雑誌として、大きな役割を担ったのだ。

However, when we consider the relationship between Olive and “kawaii” culture, there is one issue that can’t be ignored. This issue, as Sakai points out, is that the words “kawaii”, or any particular slogan for that matter, were rarely seen on the cover of Olive. In the last volume we stated that the word “kawaii” born from consumerist society became a symbol, and that it awakened a desire in girls. But despite not using this specific symbol, Olive became a leader of “kawaii” culture. How exactly was this possible?

だが、かわいいカルチャーと「オリーブ」の関係性を考えるうえで、避けて通れない問題がある。それは、酒井も指摘していることだが、「オリーブ」の誌面には「かわいい」という文字、あるいは、標語がほとんど見られないことだ。前々回から、消費社会が誕生するなかで、「かわいい」という言葉はひとつの記号となり、少女たちの欲望を喚起するようになったと述べてきた。だとすると、「オリーブ」はそうした記号を用いることなく、かわいいカルチャーを牽引してきたことになる。それはどうやってだろうか。

Let’s revisit Madoka Yamasaki’s memoir. She wrote, “I really wanted to be like the heroine in this magazine’s story. That was the impression Olive left on me after first reading the magazine when I was 13.” There was a story entwined in Olive, and it was the story of “kawaii” rife with romanticism and fairy tales. The Lyceenne were the heroines of the story, and readers strived to be like them. In this way, “kawaii” became the story of Olive, and became the raison d’etre (the purpose) behind each desired volume.

最初の山崎まどかの回想録に戻ろう。山崎は言う。「この雑誌の物語の主人公になりたい。13歳の時、初めて『オリーブ』を読んで、そんな風に思った」、と。「オリーブ」には物語があった。それはロマンティシズムとメルヘンに貫かれた「かわいい」物語だ。「リセエンヌ」はその主人公であり、読者じしんのありうべき姿だった。こうして「かわいい」は「オリーブ」という物語によって、欲望すべき記号から、レーゾンデートル(生きるための価値)そのものになったのだ。

So “kawaii” went from a symbol to a story. “Kawaii” has had a great impact on magazine culture. On the other hand, it began to appear mainstream in an entirely different form, as seen on TV and with idols. But what did it look like after making its way through the CRT? In our next volume, we’ll pick up from here.

記号から物語へ。雑誌文化のなかで「かわいい」は大きく躍動した。一方、それはまた違った形で、メインストリームに現れることになる。テレビのなかの、アイドルたちの姿。「かわいい」はブラウン管のなかに映し出されるとき、どのような姿になるのか。次回に続く。

Translated by Jamie Koide

Sponsored Links

Runner’s〜Pai? Gravure Idols on a Treadmill by Japan’s Most Notorious Pool!

Risa Satosaki Reveals Everything in the MV for “S!NG”!