For Comfort on a Budget; GU’s PJs Are Popular Among Japanese Girls

Sponsored Links

How exactly did the concept of “kawaii” come about? Last volume we searched for its origins. Apparently it was an older form of the world “utsukushi”. It meant “to adore small or childish things” and from there, for example, the story of Kaguya-Hime, or the Moon Princess, was born. We also discussed how the Moon Princess became the original base for Pokemon or other miniaturized “kawaii” culture characters today. But when exactly did this culture begin to blossom? That’s exactly what we want to ask in this volume. So how long did we have to wait until “kawaii” culture finally blossomed?

「かわいい」はどうやって誕生したのか。前回、私はその起源を探し求めた。どうやらそれは「うつくし」という古語にあったようだ。その「うつくし」という言葉が持つ、「小さなものや幼いものを愛でる」という意味合いのもとで、例えば「かぐや姫」の物語が生まれたのだった。この「かぐや姫」こそが、ポケモンなどのミニチュア化した「かわいい」キャラクター文化の元祖だということは、既に論じた通りだ。では、「かわいい」文化はいつ開花したのだろうか。いや、ここではこう問うてみよう。「かわいい」文化が花開くまで、私たちはどれくらい待たなければならなかったのか。

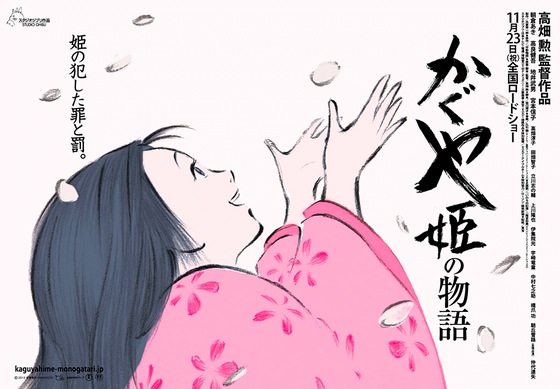

Anime about “Kaguyahime” story by Studio Ghibli

Although the word “kawaii” was included in the positive meaning of words like “utsukushi”, “to admire small and childish things”, it evolved from negative words like “kaohayushi”, meaning “so pitiable one can’t stand it”. Then sometime around the 19th Century, the word started being used in almost the same way we use it today.

「かわいい」という言葉は、「うつくし」に含まれていた「小さなものや幼いものを愛でる」という肯定的な意味が、「恥ずかしくて見ていられない」という否定的な意味を持った「かおはゆし」のような単語に乗り移ることで進化を遂げていった。そして19世紀頃になると、現代とほとんど同じ用法として使われるようになったのだ。

However “kawaii” didn’t soon become a facet of Japanese culture on its own. At the beginning of the modern age there was no “kawaii culture”. I feel rather confident saying this.

だが、こうして「かわいい」が力を身につけていった結果として、すぐにひとつの文化となったのかといえば、そうではない。近代という時代には「かわいい」文化は無かった。私はそう言い切っていいと思っている。

It had to do with the concept of “girls”, and is deeply entwined with the culture they created. What I’m saying is that “kawaii” culture was born through the “girls” from each period in history. A “girl” is born. The “girl” concept lies somewhere in the framework of a “child” and can be captured. What exactly is a “child”, though? Most of us would probably reply that a child is “a human born that has yet to become an adult”. However, at the beginning of modern times a child wasn’t viewed that way. The way we view children now was established after that.

このことは「少女」という概念の誕生、そして彼女らがつくりあげる文化の中身と深く関わっている。というのも「かわいい」文化とは、いつの時代も「少女」たちによって担われていたからだ。「少女」の誕生。それは「子ども」とは何かという考えの枠組みのなかでとらえることができる。「子ども」とはなんだろうか。そう問われれば、「生まれてからまだ大人になっていない人」というのが私たちにとっての一般的な答えだろう。しかし、近代以前の考え方では「子ども」はそのような見方をされていなかった。いまの私たちの「子ども」観は近代以後に成立したものなのだ。

According to the idea of French historian Philippe Aries, prior to the 17th century, children were viewed as “small adults”. As “small adults”, they were seen as a weaker presence that could not care or fend for themselves. After they had matured to a certain extent and were able to take care themselves and others around them, they were regarded as “young adults”. And so, their play and work was in the same place as other adults, and they were made to experience the same things. “Small adults” and “young adults” began to be described to as “children” or “childhood” through the creation of the modern concept of family and school. In short, education became a must within the institutions of family and school, and the thought that their existence as children should be protected was born. That is to say roughly that, before the modern era, until they became full-fledged adults that children spent their time maturing among adults as sort of a training period, and that in contrast following the modern era with the institutions of family and school, the result was that “children” were isolated from people of other ages, and step-by-step were protectively brought up.

これはフィリップ・アリエスというフランスの歴史学者の考え方だけれども、17世紀より以前には子どもは「小さな大人」とされていたらしい。「小さな大人」とは、自分で自分の面倒を見ることができない弱い存在のこと。もうちょっと成長して、ある程度、自分の身の回りの世話ができると今度は「若い大人」とみなされるようになった。そして、遊びも仕事も大人たちと同じ場所で同じように経験することになるのだった。「小さな大人」や「若い大人」が「子ども」あるいは「子ども時代」と言われるようになるのは、近代になって家族や学校という考え方ちゃんと成り立ってからだ。つまり、家族や学校という制度のなかで教育されるべき存在、保護されるべき存在としての「子ども」という考えが生まれるようになるのだ。まあ、ざっくりいえば、近代以前は一人前の大人になるまでは、修行期間として大人と一緒に過ごしながら成長しなさいと考えられていたのに対し、近代以後は家族や学校という制度ができて、その結果として「子ども」は他の年齢の人々と隔離され、ステップを踏みながら守り育てられるようになったということである。

Children born in modern times are treated the same as “girls”. For example, according to critic Eiji Otsuka’s idea of a “girl”, since biologically they meant to become mothers, they are protected among the institutions of family and school, they do not need to work, nor participate in social or productive activities, and that in a sense, these girls are held in a “moratorium” period. And thus, in this “moratorium” period she was bound to get caught up in a world of hobbies. As a result, girls formed their own culture, or “girls’ culture”, yet we cannot claim this as “kawaii culture”. So what exactly was this “girls’ culture” that they had created?

「子ども」が近代以降の産物だとしたら、「少女」もまた同じである。例えば、批評家の大塚英志は「少女」という考え方には、生物学的には母親になることができるのに、家族や学校という制度のなかで保護され、働かなくてもいいし、何も社会的に生産的な活動をしなくて良い、そんな「モラトリアム」な期間にいる女の子、という意味合いがあると言う。そしてこの「モラトリアム」期間に、彼女たちは趣味の世界に拘泥(こうでい)するのだ。その結果として「少女」たちはひとつの文化、いわば「少女文化」を形作るわけだが、それは「かわいい」文化には成り得なかった。では彼女たちの作る「少女文化」とはなんだったのだろう。

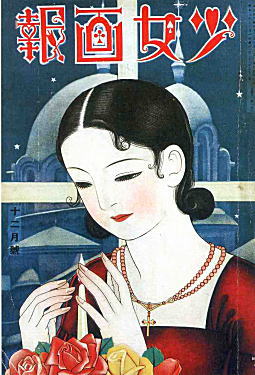

At the beginning of the 20th century, girls didn’t work, did not produce anything, only received education, and in this so-called “moratorium” period and read girls’ magazines or girls’ novels that were being serialized at the time, especially ones like Shoujo Gahou (1912 – 1942), Shoujo no Tomo (1908 – 1955), and Shoujo Kurabu (1923 – 1962). Later this transformed in to girl’s comments.

20世紀の初め、「少女」たちは、働かない、何も生産しなくていい、教育だけを受けている、そういう「モラトリアム」な期間に、少女雑誌やそこに連載されている少女小説といわれるものを読んでいた。具体的には「少女画報」(1912年~1942年)、「少女の友」(1908年~1955年)、「少女倶楽部」(1923年~1962年)などだ。それがやがて、今の少女漫画へと姿を変えていく。

少女画報

少女の友

少女倶楽部

Isn’t this what we could call the “kawaii” culture of today? When we look at it from this angle, we can see parts of the “kawaii” culture that this essay is based on, here and there in “girl’s culture”. But I can’t help but think there’s a difference. Although there isn’t enough time for us to examine the contents of these magazines specifically, Masuko Honda, the so-called expert on “girls’ theory” says that, “girls’ culture” deals with, first of all, “the color, the smell, and sound”. In other words, girls were moved by the colors, smells, and sounds described in the novels they read. Additionally, visual images, like “bows and ruffles”, were symbols of “girl’s culture”, and modern girls seem to prefer things that are frilly like bows and ruffles.

では、それは私たちの言う「かわいい」文化ではなかったか。この辺を調べていると、この「少女文化」こそが「かわいい」文化の起源であるという論文が散見される。でも、私はやっぱり違うんじゃないかと思う。時間もないので雑誌の中身を具体的に見ていくことはできないが、本田和子(ほんだますこ)という、「少女論」の第一人者に言わせると、「少女文化」の特徴は、まず「色とにおいと響き」にあるという。つまり、「少女」たちは色、におい、音の響きを小説のなかから読み取って、そこに感動していたのだ。また、「リボンとフリル」のような視覚的なイメージが、当時の「少女文化」のシンボルであり、近代的な「少女」たちは「リボンとフリル」のような「ひらひらとしたもの」を好むという志向を持っていたようだ。

From their Honda says that the sensitivities of modern girls can be summarized in the word “hira hira”, or something that frills or flutters. These frills and flutters aren’t only found among bows and ruffles, but the sensitivities of girls are like that of a dream, where they flutter beyond reality in a dream-like world. In short, girls like things that appear to “flutter”, and while being pushed out in the regular (masculine) world, they’ve made this drifting, called “fluttering”, their hobby.

そこから本田は近代の「少女」たちの感受性を、「ひらひら」という言葉に集約できるという。この「ひらひら」とは「リボンとフリル」の形状のことだけではなく、「少女」たちの感性がまるで夢を見るように、現実を越えて夢想の世界を「ひらひら」と漂うことを意味している。つまり、「少女」たちは「ひらひら」した見た目の物を好み、日常の(男性的な)世界をはみだしながら「ひらひら」と漂うことを趣味としたのだ。これが近代の「少女文化」である。

Of course, Honda’s take on girls is a little narrow. Modern girls not only “flutter”, they “zuka zuka”, or “dive in without hesitation”, like with the Takarazuka Revue. Same as those who played the male roles in the Takarazuka Revue Company, these modern girls also possessed the sensibilities that made them prefer things without restraint. “Hira hira” and “zuka zuka”. Shinji Miyadai, a sociologist, says that when you think of them together, basically modern girls idolize things that are “clean, proper, and beautiful”, and that this was a characteristic of the first “girl’s culture”.

だが、もちろん、この本田の「少女」論にはケチがつく。近代の「少女」たちは「ひらひら」していただけではない、「ヅカヅカ」もしていたのだ、と。「ヅカヅカ」とはなんとも変な言葉だが、要するに宝塚歌劇団のことである。「少女」たちは宝塚歌劇団の男役のように、「ヅカヅカ」としたものも好むという感受性も持っていたのだ。「ひらひら」と「ヅカヅカ」。宮台真司という社会学者はこれらを合わせて考えると、つまり、近代の「少女」は「清く正しく美しい」ものを理想としていて、それが初期の「少女文化」の特徴だったといえるのだ。

This was, anyhow, different from “kawaii”, or an “adoration of small or childish things”. Because of that, we cannot say that “girl’s culture” is the same as “kawaii” culture. “kawaii” was not born from girlish sensibilities. Its explosive birth had to be put off until the arrival of consumerist society. So in our next volume, I’d like to describe the birth of consumerist society and “kawaii” culture. There we will have finally arrived at the stage where “kawaii” culture could blossom.

いずれにせよ、それは「かわいい」という「小さなものや幼いものを愛する」感性とはまた別のものだった。だから、近代の「少女文化」は決して「かわいい」文化ではなかったのだ。彼女たちの感性からは「かわいい」ものは生まれない。それが爆発的に生み出されるようになるのは消費社会の到来を待たなければならないのだ。次回は、消費社会と「かわいい」文化の誕生について説明したい。ようやく、「かわいい」文化は花開く時が来るのだ。

Translated by Jamie Koide

Sponsored Links

Breaking News : Hina Aizuki to Graduate From 3min. at April 2nd Live!

8th Wave of Tokyo Idol Festival 2016 Performers Announced!!