For Comfort on a Budget; GU’s PJs Are Popular Among Japanese Girls

Sponsored Links

In this series, we’ve referred to the “kawaii” (“cute”) revolution born from Japanese consumerist society in the 70s as the first wave of the “kawaii” revolution. Finally this revolution, with the aid of girls appearing on screen, tightens its hold on Japanese society. And so, the power of “cuteness” plants itself among idols. In order to explore the relationship between idols and “kawaii” culture, both in the previous volume and this one, I’d like to take the time to consider the differences between 70s and 80s idols. I have a hunch that the “kawaii” revolution first began to idols in the 80s, giving rise to the question of how they differed from each other during this time.

70年代の消費社会が生み出した「かわいい」ムーブメントを、この連載では第一次「かわいい」革命と呼ぶことにした。この革命は、やがて、ブラウン管に映る女の子たちの力を借り、日本社会のなかでの影響力を強めていった。アイドルに「かわいい」の力が宿ったわけだ。前回と今回は、このアイドルと「かわいい」文化の関係を探るために、70年代と80年代のアイドルの違いについて考えることに時間を割いてみたい。というのも、筆者は直感的に、「かわいい」革命がアイドルをも巻き込むようになったのは、80年代からなのではないだろうか、と思っているからで、その時に、じゃあ、70年代と80年代のアイドルの差って何なのだろうか、という疑問が湧いてくるからだ。

Read the previous volume/前回の記事を読む

Read older posts

vol.1 : Finding Where “Cuteness” Currently Lies

vol.2 : What is the Exact Origin of “Kawaii”?

vol.3 : Kawaii Culture Didn’t Exist at the Beginning of the Modern Age?!

vol.4 : Consumerist Society and the Birth of “Kawaii” Culture

vol.5 : The Word “Kawaii” Becomes Just for Girls, to Re-affirm Their Girliness

Vol.6 : The Magazine “Olive” Made Japanese Girls Aware of The Rare Value of Girlhood and Maidenhood

To answer this, last time we took a look at Momoe Yamaguchi, who represented idols of the 70s. In this installment, I’d like to focus on Seiko Matsuda, who arrived on the scene at the heels of Yamaguchi’s retirement, and stood at the top of the idol-on-idol entertainment industry

そのために、前回は70年代の代表的アイドルの山口百恵について考えた。今回は、百恵の引退と踵を接するように登場し、以後アイドルオブアイドルとして芸能界のトップに立ち続けた、松田聖子を中心に考えてみたい。

Seiko Matsuda, or idols who came after her, would play the role symmetrically opposite to Momoe Yamaguchi’s. After debuting in 1980 with “Kaze wa Akiiro”, Seiko Matsuda would go on to represent idols from the 80s in both literally and figuratively, with 24 number-one singles on the Oricon chart over the following eight years. Without any gap, Seiko Matsuda soon filled the shoes Momoe Yamaguchi had left behind in the eyes of Japanese society.

松田聖子、あるいは聖子以後のアイドルたちは、ある意味では山口百恵と対称的なアイドルを演じていくことになる。松田聖子は1980年に「風は秋色」でデビューすると、以後8年間、24曲続けてオリコンチャート1位を獲得し、名実ともに80年代を代表するアイドルに君臨した。山口百恵を喪失した日本社会の大衆は、休む間もなく松田聖子という新しいアイドルを獲得したのだ。

One reason for Matsuda’s popularity was her “burikko” (overly cute and innocent) character. Her too-cute, “burikko” character was one that really appealed to young women. This is because, unlike Yamaguchi’s real, yet raw story, anyone (to a various extent) could copy Matsuda’s “burikko”. Later, girls would be also be unable to sustain from copying her hairstyle, called the “Seiko-chan cut”.

松田聖子の当時の人気のひとつに、「ブリッ子」キャラというのがある。彼女の生み出した「ブリッ子」という過剰にかわいさを演出するキャラクターは、若い女性を中心にとてもウケた。というのも、百恵の「リアルな生の物語」とは異なり、聖子のぶりっ子は誰でも(というと語弊があるかもしれないが、上手い下手は問わず)真似ができるものだったからだ。また彼女のヘアースタイルを「聖子ちゃんカット」と言い、こちらも真似をする女の子たちがあとを絶たなかった。

Even Miyuki Watanabe (NMB48) copied Seiko-chan hairstyle for her solo single released in 2014.

Above all else, Seiko Matsuda was cute, and this cuteness was something people wanted to imitate. In this way Matsuda, apart from her powerful voice, was able to use the symbol of “cuteness” as her weapon and climb to the top of the idol world.

松田聖子はとにかくかわいい。そしてそのかわいさは、真似したくなる、そのようなものだったのである。ようするに、松田聖子は、その圧倒的な歌唱力とは別に、「かわいい」という記号を自分の武器として駆使し、アイドルの頂点に登り詰めたのだ。大塚英志はこのことを、別の言い方で次のように指摘している。

Seiko Matsuda demonstrated the rare talent of being able to turn her “girliness into a simulation. (Excerpt) By turning being a girl into a kind of program, Matsuda was able to acquire an even purer girliness. Before long, those who criticized her as a “burikko” would become her supporter “ (System to Gishiki / Systems and Rituals)

「少女である自分をシミュレーション化していくことに稀有の才能を発揮したのは松田聖子である。(中略)〈少女〉をプログラム化することで松田聖子は、かえって純化した〈少女〉性を獲得した。『ブリッ子』と非難した女の子たちがやがて急速に聖子支持へと回るのはそれ故である」(『システムと儀式』)

Eiji Otsuka doesn’t use the word “kawaii”, but we can take this girliness to mean cuteness, and interpret it as retaining it semi-permanently even as an adult.

大塚英志は「かわいい」というワードを使っていないが、ここでいう〈少女〉性とは「かわいい」を志向し、その極地を目指すことによって、大人になることを半永久的に留保し続けるというありかただと解釈できる。

Yamaguchi sought to protect her own real image. Matsuda would turn everything into a simulation of a virtual image. In short, she presented herself as someone easy to copy, and she wasn’t alone. All the idols that came after here exemplified an simply understood “cuteness” that could be mass-produced.

山口百恵は自分のリアルな像を守ろうとした。松田聖子はそれを虚像としてすべてを「シミュレーション化」していく。つまり、コピーしやすいものとして提示する。松田聖子だけではない。聖子以後のアイドルたちはみんな、大量生産可能な「かわいい」をわかりやすく表現していったのだ。

Take for example, Noriko Sakai, who debuted in 1986. She was able to appeal to people by using her own, cute, “Noripi language” with words like “yappii”, “itadakimammoth”, and “urepii” (cute plays on the words “yay”, “let’s eat”, and “glad”). Because young women imitated these words, they quickly gained popularity and became buzzwords. I even remember my mother using these words with me when I was little, and feeling embarrassed by them as a child.

例えば1986年にデビューした酒井法子。彼女は「ヤッピー」「いただきマンモス」「うれぴー」などといった可愛らしい言葉である「のりぴー語」を使うことでアイドルとしての人気を高めていった。「のりぴー語」も若い女性たちが真似をすることで一気に大衆性を帯び、流行語になったのだ。筆者の母親も、筆者が幼少時にやたらと「のりぴー語」を使っていて、子供ながらにちょっと気恥ずかしかったのを覚えているくらいだ。

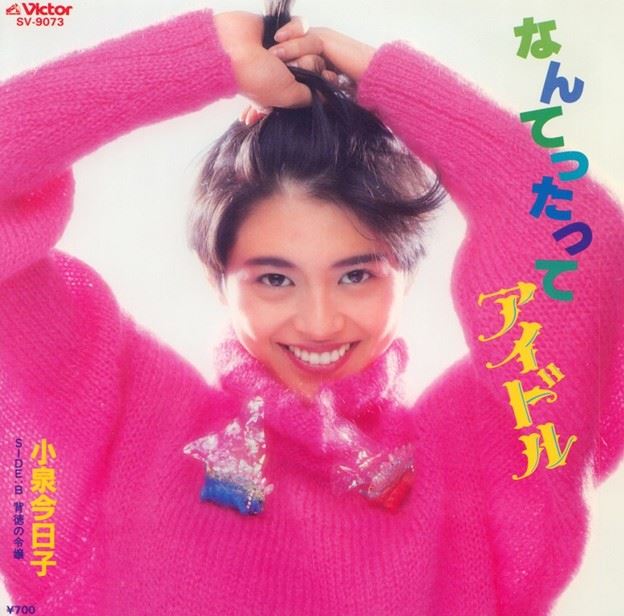

Kyoko Koizumi is another example. Her major hit song in 1985, “Nantetatte Idol”, just as Eiji Otsuka describes it, is “very much a piece where she sings about the delight of living as part of an idol simulation”, and even watching it now and being aware that she plays a fictional idol, she takes great pleasure from it.

あるいは、小泉今日子。彼女の1985年の大ヒットソング「なんてたってアイドル」は、やはり大塚英志がいうように、「まさにシミュレーションとしての〈アイドル〉を生きることの気持ち良さを歌った快作」であり、いま映像を見ても、そこにはフィクションとしてのアイドルを演じていることを自覚し、それを声高に叫ぶことで快楽を得ようとするアイドルの姿が映し出されている。

In other words, in the 80s, cute idols themselves became a symbol, and so, the difficulties associated with performing as an idol disappeared. No more were the idols of the 70s, who had to gain support by spreading the realness and goodness of their human character. In this manner, the first wave of the “kawaii” revolution changed what an idol ought to be, creating the subsequent prototype still used today.

つまり、80年代、「かわいい」アイドルそれじたいがひとつの記号となったのである。だから、アイドルを演じることだって、何ら困難なものではなくなる。それは、70年代のリアルさ、人間として立派であることを喧伝することで支持を得ようとするアイドルでは、もはやないのだ。第一次「かわいい」革命はこうしてアイドルのあり方を変え、今にも続くアイドルの原型を作り出したのである。

Of course, this isn’t to say that idols in the 70s weren’t cute. If you watch footage of Momoe Yamaguchi, you’ll see she’s cute. However idols didn’t use “cuteness” as a symbol, nor did their fans look for “cuteness” in their appeal. Analyzing critic Masaaki Hiraoka’s “Momoe Yamaguchi is Buddha” there is proof that the word “kawaii” barely registers.

じゃあ70年代のアイドルはかわいくなかったのかと言われれば、もちろんそうではない。山口百恵だって、当時の映像を見ると、かわいい。しかし、彼女たちは「かわいい」ということを記号として用いることはしなかったし、そのファンたちも、彼女らの魅力を「かわいい」というところに求めようとはしなかった。山口百恵の魅力を批評的に分析した平岡正明の『山口百恵は菩薩である』に、「かわいい」という言葉がほとんど出てこないのが、その証拠だ。

Idols decidedly turned the symbol of “cutness” into a commodity or cultural property. It is at this point that the first wave of the “kawaii” revolution, born from consumerist society in the 70s, would meet its demise. Beginning with the character-themed items created by Sanrio and the like, this revolution led to the establishment of a number of girls’ magazines, and the creation of idol culture. Here things surrounding “kawaii” settle down for a bit, but then heading into the 90s, begin to spiral again amongst the wave of globalism.

アイドルを「商品」にしたのは、ずばり、「かわいい」という記号性、あるいは、文化性なのだ。ここに来て、70年代の消費社会のなかで起きた第一次「かわいい」革命は、終焉を迎える。サンリオなどのキャラクターコンテンツから始まり、数々の少女雑誌を生み出したこの革命は、アイドル文化を作り出すまでに至った。そして、「かわいい」を取り巻く様々な事象は、ここで一旦落ち着き、90年代に入って、再び大きな渦を巻き始める。そう、グローバリズムという波のなかで。

Translated by Jamie Koide

Sponsored Links

Just Another Day in the Park for BILLIE IDLE® in the MV for “Nakisou Sunday”!

Risa Satosaki Reveals Everything in the MV for “S!NG”!